I was speaking at an AEI dinner a couple of nights ago, and the questions focused mainly on Ukraine, Iran, and tariffs. In each case, the guests expressed confusion about what Donald Trump is up to. What’s his strategy?

Trump and I are not close personal friends (or friends at all), but having watched the recent blowout with Ukraine extremely closely, and examining his record in his first term and since inauguration, a few things are clear.

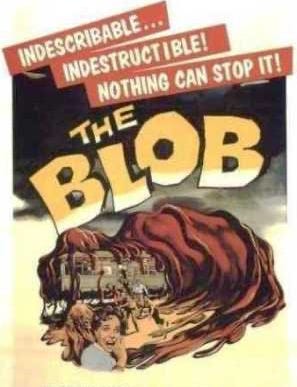

Donald Trump is not one of “us”: Us means those of us who are immersed in Washington, have lived here for decades, know cabinet officials and members of Congress and think tank denizens and ambassadors… the so-called swamp, or if you can tolerate Ben Rhodes, “the blob.” What does that mean? It means Trump doesn’t think about foreign relations through the prism of diplomacy or trade. He thinks through foreign relations, whether economic or political, through the prism of his own self view: dealmaker. Through this prism, he deals with adversaries and friends as if he is selling a building or a casino.

Donald Trump thinks of himself as an entrepreneur/president. What does that mean? It means he wants his parties to be happy unless he identifies them clearly as an enemy. He may screw them in the end, but at the beginning, everyone should have danish at the table. A coke. Maybe some McDonalds. That means, he has explained to, for example, Ukrainian President Volodymr Zelensky, that he is going to say nice things about Putin. Because he wants peace. It means that unless crossed, he will say nice things about Zelensky. Having been crossed, Trump is less inclined to praise the Ukrainian leader. But if you read his remarks at the outset of the infamous Oval meeting, you’ll see that approach.

Donald Trump loves leverage. This is the passion behind tariffs. Anyone who thinks about economics from the standpoint of global commerce, international economic relations, and theory understands that tariffs are almost universally bad. Even retaliatory tariffs tend to punish not simply the tariffee, but also the tariffer. But if that’s not how you think about the world, and you believe that everything boils down to dealmaking, then having the most leverage is clearly an advantage. What are tariffs? Leverage. You do what I want, or I punish you. Does the bizarre on again/off again levying and then lifting of tariffs against Mexico, Canada, and China risk Trump appearing capricious? The boy who cried tariff? You bet. Does it also risk retaliatory tariffs? Ditto. Does it risk inflation for Americans and a loss of credibility for both the dollar and the U.S. economy? Indeed. But if you see this as a necessary evil on the road to a good deal, then you advertise the downturns as speed bumps rather than structural harms. QED.

We can argue against this view of the world, and many of us have done so repeatedly. We can also argue that when one makes nice with an enemy of the United States — Putin, for example — he is more likely to misinterpret intentions and to believe he has license to do more bad things. (If you have doubts about this, check out Russia’s latest support for Iran.) We can argue that one can ignore economic theory, but cannot ignore the historical facts of tariff wars and their troubling denouement.

Trump and his acolytes will counter that tariff threats have caused the Mexican government to take seriously the problem of illegal immigrants flooding America across its border. That is undeniably true. (Threats to act militarily against cartels probably also made a difference.) And in the case of Mexico, it’s true that the United States has a lot of leverage, both economic and political. The same is true of Panama, where China has been summarily bounced from the Canal. But is the same true of Europe? Russia?

The problem for Trump with this view of a transactional world is that it fails to appreciate that there are countries with which one cannot deal. Iran is one. Russia is another. China, unfortunately, is too. In business, the dealmaker rarely confronts ideological dogma. In foreign policy, sadly, we see ideology all the time. And if your theory of the world fails to understand that Putin, Xi, and Khamenei may make tactical concessions, may lie, may temporarily play ball, but that their end game is not simply antithetical to your own, but dangerous to America, you may end up doing business and misinterpreting people who are not simply difficult, but evil.

Looking outward from the swamp at Donald Trump’s statements and decisions, it’s easy to see how the blob itself believes Trump naive at best, malign and proto-fascistic at worst. Especially when a class-driven, establishment snottiness means a predilection to think that way anyway. (Yes, we know Donald Trump considers himself the uppest of the upper classes, but the chattering classes and glitterati of Washington disagree; to them, he is a “bounder.”) We can also see that NYTimes columnists and their ilk are uninterested in considering that Trump may not admire Putin, but may be flattering him for tactical purposes.

Could all of this analysis be wrong, a rosy read on a man who is at heart a wannabe dictator, who genuinely does like Putin? And Xi? And Kim Jong Un? Sure, anything is possible. But it is hard to reconcile Donald Trump’s uncanny ability to read the public, and to understand markets in public opinion, and yet completely misread adversaries of the United States. We shall see soon enough, as we move towards a “peace” between the Kremlin and Kyiv.

###

A few other notes on current events. You may have seen the Financial Times (and subsequent other) headlines trumpeting Europe’s new resolve in expropriating Russian cash — cash they have sat on and in some cases stolen for their own benefit. Don’t believe it. I asked Stephen Rademaker (coincidentally my spouse, and the best government lawyer I know) for his take. He explains:

The lead story in Tuesday’s Financial Times was headlined “Europeans move towards seizing €200bn of frozen Russian assets”. What the story goes on to describe, however, is the antithesis of a plan to confiscate frozen Russian assets for the benefit of Ukraine. Instead, it describes a French-led plan to enforce any ceasefire in Ukraine by pledging to confiscate the frozen Russian assets if Russia violates the ceasefire agreement.

This is a great plan for Europeans who are looking for an alternative enforcement mechanism to deploying peacekeeping forces to enforce a ceasefire agreement. And also a great plan for European central bankers who are determined to prevent the Russian assets from ever being confiscated for the benefit of Ukraine, no matter how much damage Russia does. But it is most certainly not a plan for actually confiscating those assets.

If adopted, what this plan would mean in the first instance is that the assets cannot be confiscated now, because they must be preserved as the enforcement mechanism for a ceasefire agreement that may or may not materialize in the coming months or years. And if a peace agreement is reached, again the assets must not be touched for so long as Russia continues to respect the agreement. And, of course, no one will want Russia to violate the agreement, meaning that everyone will implicitly be hoping that the assets remain right where they are today. And for Russia to take any of this seriously—for it to be actually deterred from violating the ceasefire agreement by the threat of asset confiscation, Russia needs to be assured that at the end of the process—presumably many years in the future—the assets will actually be returned to Russia rather than made available at the point to the victims of Russia’s aggression.

So far from being a plan to confiscate the frozen Russian assets, it is actually a plan to deprive Ukraine of them and return them safely to Russia at some indeterminate point in the future.

If you understand that this rather nefarious European “plan” is merely masquerading as new, Trump-induced resolve over supporting Ukraine, you may also ask yourself whether other European pledges — €800 billion in new defense spending! — are real. And the answer is… maybe. If that money is intended to purchase U.S. arms, then perhaps Europe can help Ukraine. But that seems less than likely. And Europe doesn’t make enough of what Ukraine needs, or have it in stockpiles, to actually have that money make a difference NOW, when Ukraine needs it.

###

One last note: Yesterday, President Trump met with a group of hostages freed from Hamas. He was obviously moved, and subsequently announced:

So, is that U.S. policy? The Trump administration has also rejected the new Arab plan for Gaza, which envisions a Palestinian Authority government and some new buildings, but which has no plan to disarm Hamas.

Or is this U.S. policy?

The Trump administration has been holding direct talks with Hamas over the release of U.S. hostages held in Gaza and the possibility of a broader deal to end the war, two sources with direct knowledge of the discussions tell Axios.

Good question. I’ll be writing more on Gaza next week.

NB Last week, I made comments available solely to paid subscribers. This is with a view to actually addressing your thoughtful comments, and restricting the occasional troll. DP

I'm currently reading "Churchill's Citadel" by Katherine Carter. Focused on the days before Hitler invaded Chechoslovakia. Many parallels between Hitler and Putin. And, sadly, thinking Trump is the Chamberlain of our times.

Very good as usual. Why is it so difficult nowadays to recognize certain principles as truths in "diplomacy." A good grounding in history is essential. Take care.